Today is Valentine’s Day. How many men will lose their heads over women (and vice versa)?

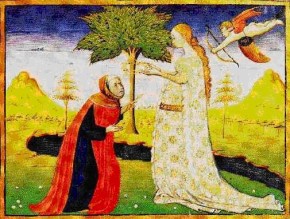

When we write gushy sentiments on Valentine’s cards about our beloved’s power over us, we owe a debt to the 14th century poet Francesco Petrarch, who wrote 366 love poems to the woman he adored. They were more about his own feelings than Laura, a married woman above him in station. This psychological focus made them the first “modern” love poems and they made Laura immortal, though nobody knows who she was. The best guess is Laura de Sade, whose descendent, the Marquis de Sade, behaved so naughtily that he had an “ism” named after him.

Petrarch’s poems were full of elaborate comparisons called Petrarchan conceits in which he compared his lady’s eyes to stars or suns, whose rays warmed him. When her gaze turned elsewhere, he froze. He was a rudderless ship on a storm-wracked ocean, desperate for the guiding light of his lady love. Her hair was golden, her skin ivory, and her voice sweet.

Like convenient hashtags, these phrases were used and misused by the poets who followed, notably the Tudor sonneteers, Wyatt, Howard, Sidney, and Spenser. By the end of Elizabeth’s reign, at least one famous sonneteer was mocking Petrarch. In sonnet 130, Shakespeare says,

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

But Shakespeare also used love conventions when it suited him and claimed that his poetry would immortalize his beloved, a young man. “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” he asked. Let’s hope this flattery squeezed more money from his patron, Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton. Two hundred and fifty years later, Elizabeth Barrett Browning was one-upping Shakespeare, asking, in poetic hyperbole, “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways. I love thee to the depth and breadth and height My soul can reach”.

In a kind of poetic justice, Francesco Petrarch literally lost his head. In 2003, professors digging up Petrarch’s bones in Italy discovered that the skull had disappeared. The Guardian commented that “The suspects in a literary whodunnit spanning almost 700 years include a bibulously larcenous 17th century friar, and a supposedly clumsy 19th century anatomist.” Curiously, the suspect tried to cover up the theft by substituting a woman’s skull. Was it Laura’s? Doubtful, since unlike other famous lovers, the pair were not buried in the same grave, although early fans agitated to get their bones mingled.

Haunted by this idea, I wrote a scene in my novel Muse in which Petrarch, having learned of Laura’s death, rides his horse nonstop from Parma, Italy to throw himself on Laura’s grave in the de Sade chapel in Avignon. Did he stop writing sonnets to her? Not a bit of it. Having written 266 poems about Laura in Life, he turned another page and wrote a hundred more about Laura in Death.

Some ideas just never die. Happy Valentine’s Day!