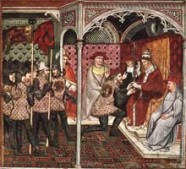

Muse is set in medieval Avignon during the period when the popes resided there, rather than in Rome. Writers such as Francesco Petrarch flocked to the city to seek patronage from the Pope and cardinals. The city was bursting with craftsmen, merchants, goldsmiths, and money lenders as well as the architects, master masons, and artists who worked on the Pope’s immense palace. Under Clement VI, who appears in Muse, the palais des papes became the most celebrated court in Europe, a salon for the artists, musicians, and intellectuals who were the avant-garde of the Renaissance.

At the beginning of the 14th century, Avignon was a city of 5,000 people. It grew by a thousand a year as men came to the papal city to seek their fortune and curry favour with the Pope, who was centralizing religious power in himself. The Pope behaved more like a monarch than a spiritual leader. The main symbol of his opulence was the palace itself. He needed a fortress to ward off his enemies (which included fringe groups like the Cathars, the Knights Templar, and the poor Franciscans), to protect the vast revenues he collected, and to house about 500 officers, guards, and servants.

Most of the palace construction was done under two popes, Benedict XII and Clement VI. Before he became Pope, Benedict XII was one of the inquisitors who eradicated the Cathars. His successor, Clement VI, was more genial. He expanded the palace to the grand fortress that now greets visitors to Avignon. A nobleman who moved his extended family into the palace, he promptly set about promoting his male relatives to marshals, archbishops, and cardinals. This was nepotism of the highest order and ensured that the men closest to him remained loyal.

Many scenes in Muse are set in the Pope’s palace. Not all the rooms are open to visitors today. Some of the most interesting rooms, like the Pope’s study, the chambre du cerf, are closed to prevent damage to the original décor. To see them, I took the secret palace tour, led by a French scholar, of the three adjoining towers that house the Pope’s private rooms. We began in the Pope’s garden and wine cellar, then explored his étuves (steam room with a lead bathtub), then the lower and higher garde-robes, and the treasury (with hidey-holes under the pavingstones). The best part was the Pope’s study, with its luxurious painted tiles, and his adjoining bedchamber, with its surprisingly pagan frescoes. Women were known to attend the lavish banquets in the Grand Tinel. How many made it as far as the Pope’s bedchamber?

The history of the Avignon popes is richly documented in the archives, but some of the best tales are the rumours that persist, even after 700 years, telling us that the popes were not puritans. Rumours are meat and drink to a novelist, and Muse is a novel in which myth and secrecy play major roles.

Petrarch was vocal in his criticism of the popes for their corruption. He called Clement VI a Nimrod (the king of Babylon) and accused him of incest with his “niece,” Cécile de Turenne. Petrarch, who led the Italian lobby to return the papacy to Rome, wrote nineteen secret letters. They were called the Liber sine nomine, letters without names, to protect the recipients. “I am astounded,” Petrarch says, “to see these men loaded with gold and clad in purple, boasting of the spoils of princes and nations; to see luxurious palaces and heights crowned with fortifications . . . . Instead of holy solitude we find a criminal host . . . instead of soberness, licentious banquets. Instead of pious pilgrimages, preternatural and foul sloth.”

The Pope wasn’t the only prelate to smuggle young women into the palace. “How hot are the old in love—how they rush to it!” Petrarch exclaims. “Such forgetfulness of age, rank, and strength! How they burn with passion, how they hurry to every dishonour, as though their every glory is not in Christ’s cross but in banquets and drinking bouts and what comes next on their scandalous couches.”

Petrarch was not the only person with a quarrel with the Avignon papacy, but he was the most important scholar of his time, and that may be why his words are still inflammatory. Much of what he wrote is too frank to quote. The church has tried to snuff it out because it reflects badly on the popes. Should we believe what Petrarch says? I think so. After all, many of the letters’ recipients were themselves priests, bishops, and cardinals. As a novelist, I had the freedom to believe Petrarch and create my version of these secrets in Muse.

This post first appeared at the blog Sukasa Reads.