Seven hundred years after the popes lived in Avignon, we can read reports about their banquets and gain insight into their luxurious life style. The type of food people ate depended on their rank. Although there was a vast difference between the diet of a pope and a peasant, the poor did not starve, because the Pope gave out 6,000 loaves of bread daily.

The staples of a peasant’s diet were grains, legumes, onions, garlic, vegetables, coarse dark bread, eggs, and milk products, with a little fish, meat, or poultry. This would be washed down with ale or watered wine, which was safer than unclean water. There was a variety of stews (soups, ragoûts, brewets, porrays, sauces, casseroles) that consisted of a little meat and many vegetables. Pies sound like stews that are poured into a pasty shell and baked. Dessert might consist of nuts and dried or cooked fruit. Tomatoes and potatoes didn’t reach Europe until the Renaissance. A rogue potato slipped into an early draft of Muse. An anachronism, it had to be rooted out and replaced with a turnip.

A merchant or guild-master would have eaten “higher on the hog,” his cut of meat coming halfway between the peasant’s and a pope’s. Foods, like people, were arranged in hierarchies from root vegetables at the bottom to imported delicacies at the top. Roasted quadrupeds were lower in status than birds, which rose from chickens up to cranes and peacocks. Salt, spices, and herbs masked the taste of rotting food. Sugar, honey, nutmeg, ginger, and cinnamon were expensive, and saffron and pepper were only for the wealthy. Kitchen hygiene was a long way in the future. Many people died from food poisoning. Other poisoning was rife as well. A noble might have a taster, or might drink from a special cup that would detect poison. Apparently, Pope Benedict XI was poisoned by figs. Pope John XXII suspected that an enemy was trying to poison him with a wax image hidden in a loaf of bread. Perhaps he was correct, because his nephew ate it and died instead.

Much can be learned about medieval eating by studying works of art, literature, and old cookery manuals, for instance Le Ménagier de Paris. Recently, the British Museum found a 14th-century manual written by the Queen of England’s cook, who had a penchant for exotic ingredients like hedgehogs, blackbirds, and unicorns. The Cluny museum garden in Paris gives us a good idea of what people grew, which, surprisingly, did include greens like lettuce.

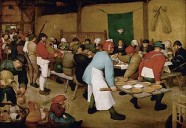

Diners sat on a bench along one side of a trestle table assembled for the meal and taken apart afterwards. One of these can be seen in the Cluny, along with medieval cooking pots, dishes, and utensils. People would eat in pairs, sharing a wine cup and using a slice of bread as a trencher for holding meat. They washed their hands in a shared bowl before they ate and observed some table manners, like wiping their hands on the tablecloth. Chaucer’s wonderful description of the Prioress’s dainty table habits suggests that her fastidiousness was rare.

Extravagant banquets were hosted by the Pope in the Grand Tinel in the palace, a dining room the size of a field. Rumour has it that one pope died by stuffing himself with eels soaked in vernaccia, a sweet wine. Another pope ate strawberries with a crystal fork, although ordinary people only used knives and spoons. A banquet given by John XXII served 55 sheep, 9 oxen, 8 pigs, 4 boars, 690 chickens, 580 partridges, 292 birds, 270 rabbits, 200 capons, 59 pigeons, 40 plovers, 37 ducks, 4 cranes, 2 pheasants, and 2 peacocks–and that was just the meat! A papal banquet with 27 courses given by Cardinal Ceccano has been made legendary by a surviving eye witness report. A fountain with five different wines issuing out of the spouts was too rich for a novelist to pass up and has found its way into a scene in Muse.

Then, as now, the greatest wisdom lay in choosing simple, nutritious fare instead of overindulging at a rich man’s table. As he aged, Petrarch grew disgusted by the excesses of the cardinals and popes and retreated to the country near Fontaine-de-Vaucluse. A letter survives in which he invites a cardinal’s nephew to a pastoral supper: “There is no market of delicacies here. It is a poet’s repast that will be waiting for you . . . Apples ripe, soft chestnuts, and a jug of fresh-drawn milk. The rest will be rougher: you will find hard and simple bread, a stray rabbit, or a crane that someone has sent to me . . . And perhaps the strong meat of a wild boar.”

In Avignon today, the tourist can enjoy a simple tartine washed down with Rhône wine or can dine extravagantly on elaborate Provençal cuisine with Châteauneuf-du-Pape, presented in a heavy bottle embossed with the Pope’s insignia. Whichever you choose, according to the status of your budget, you can be sure that you’ll be eating the best seasonal ingredients because the Avignonnais still take great pride in their cuisine.

This blog first appeared at Your Hidden Self